You are here

Phones and Nuclear Power: The Network Effect Collides with the Tragedy of the Commons

The technologies we embrace reflect social and business values. But whether they embody our personal values is another question entirely. Contrary to decades of myth-making about the inherent neutrality of technology – it is only a question of how we use it – values are embedded in many technologies, reinforcing some values while undermining others.

This realization is awkward. It challenges the core idea that technology is a benign force that springs freely from the minds of scientists and engineers and is an inherent element in the steady march of social advancement and progress for all.

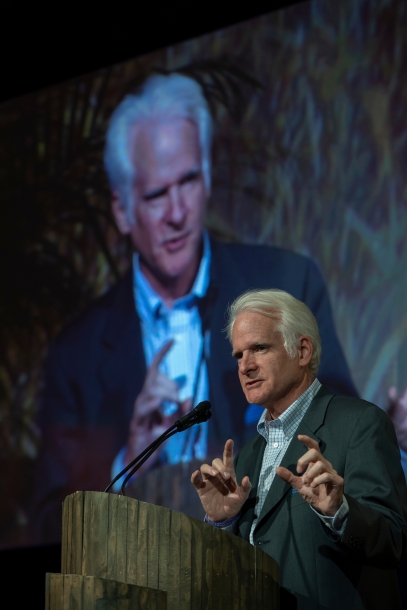

While the evolving Facebook debacle puts this in the public eye today, I had the opportunity some years back at the Aspen Ideas Festival to engage with Eric Schmidt (the then CEO of Google) about this question of technology and values. After claiming that key functions of our cell phones operate “by their nature,” he backed away graciously from this its-only-a-neutral-tool perspective. But his instinctive reliance on that claim reveals an all too common tendency among purveyors of technology; we just build the tools, how they are used is someone else’s problem.

(For commentary on this discussion, along with video of the entire panel discussion and Q & A session from the 2012 Aspen Ideas Festival Channel, please see my blog Autonomous Technology.)

That the tech community still largely claims it can ignore the social consequences that attend the appropriate and intended use of its devices is stunning. We are in an age when corporate social responsibility, the circular economy, and supply chain management are expanding “cradle to cradle” responsibility. But leaders in the technology sector are drawing from the playbooks of the tobacco and firearms companies; it's the users not the technologies themselves creating negative consequences.

The warning signs are everywhere for tech leaders who can see them.

How about nuclear power? Is this a neutral technology or is there something inherent in the technology itself that ineluctably pulls us in a certain direction? Whether in North Korea or North America, the use of nuclear materials demands, without exception and regardless of the intended use, a high level of secrecy and security. From uranium mining through to nuclear waste it demands security perimeters, special handling, and so forth. Whether you like concentrated nuclear or prefer distributed solar, the values embedded in the two technologies are profoundly different.

Before we opine on how unfair it is to compare the phone to nuclear power, and before we appeal to the democratizing impact of smart-phones and social media, let us please remember that Facebook was conceived of in 2004 as a means of ranking babes at Harvard. The baby-faced depiction of it as a neutral, social platform that just lets people connect seems to be under assault as Facebook squirms in social quicksand made up in equal parts of hubris, duplicity, and market power.

There is a deeper new reality lurking beneath questions of privacy, net neutrality, data-sharing, and how we have become accustomed to accepting “free” services with impenetrable terms of use. There is no longer a meaningful distinction between content providers, advertisers, and the architects of distribution systems. The neat distinctions and firewalls between “the pipe,” platforms, and producers of content have given way to a wickedly complex web (sorry!) of interlinked technologies.

We are in a moment of historic reckoning that is playing out in the most personal places. It can be heard in dinner table arguments about phone usage; in school yards filled with kids looking at screens; in therapy office discussions of rising anxiety and loss of emotional connection; in medical offices and skyrocketing diagnoses of Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD); in bedroom conflicts about where to put the phone.

But this moment also signals a profound conceptual clash between “The Network Effect” and “The Tragedy of The Commons.” The network effect speaks to one reality we all experience. The value of a network is closely related to how many people are in it; each new additional member adds value to the whole. Facebook as a tool limited to Harvard undergraduates was not so interesting. Add another school, and then another and another and after a few million people the network effect is clear.

Powerfully captured by Garret Hardin in his masterful essay from 1968, The Tragedy of the Commons explains what happens when too many people overwhelm a resource on which they all depend. When individual farmers use a common and limited grazing space for their herds everyone benefits when there is an equilibrium between the space and the number of animals. But if unbridled self-interest leads one farmer to enlarge his herd, thus consuming more of the commons, other farmers will be drawn to do the same thing. In the ensuing tragedy the commons is degraded and eventually destroyed. Private choices, public consequences.

Expanding the social media “commons” through the power of the network effect seems to have no limit. No technical limit, perhaps. But it is we, humans, who represent the limit. How much technology can the human commons absorb and still survive? No one wants to go back to living in caves. That is not the point. This is not a Luddite argument about smashing machines. But can we as a species manage our appetite for technology such that we don’t push past our own human carrying capacity?

Our fate may be in our hands. Literally.

- jonathan.halperin's blog

- Log in or register to post comments