You are here

Authenticity and Empathy in the American Food System

Authenticity is the touchstone of trust, the defining characteristic mentioned repeatedly at this week’s James Beard Foundation conference. From Genetic modification of food to mother’s milk, from food service providers to artisan foragers, from Nashville to Portland the exploration of trust and distrust was both deep and wide in this live-streamed conference. Farmers, businesspeople, advocates, researchers, food processors, produce distributors, chefs of global repute and journalists grappled with a system of linked but distinct problems.

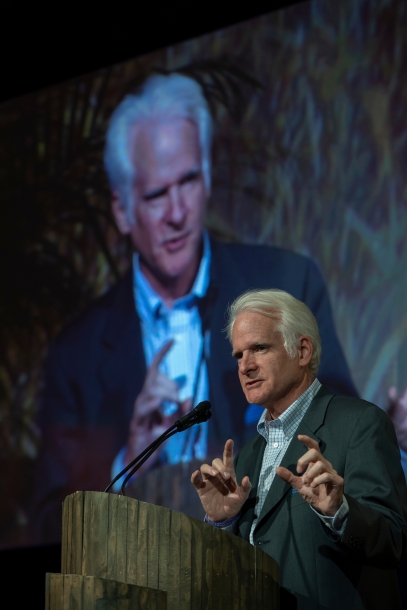

"Leadership and Trust in the Public Sector"

Panel with Sam Kass, NYC Dept of Education's Eric Goldstein

and Designing Sustainability's Jonathan Halperin

Sam Kass, Assistant White House Chef and Senior Policy Advisor, was right to observe that while change is happening within this system and its trajectory is shifting there is still no single place where one can intervene to shift the path of a food system as complex as we now have in America. And Eric Goldstein, Chief Executive of the NYC Office of School Service, was also right that these issues go way beyond ingredients to the core of how we live our lives in American today.

But first principles, simple and enduring and profound, still obtain. James Beard articulated one many years ago when we wrote that “food is our common ground.” We all eat, we all must eat, we all make choices about what we eat and these choices have consequences both personal and societal. Yet, for the 50,000,000 citizens in America who go hungry that common ground seems tenuous at best, choice severely constrained and a future deeply compromised. To draw attention to this appalling problem, hunger amidst plenty, film directors Kristi Jacobson and Lori Silverbush have made a stunning and powerful movie: A Place at the Table. And the Marcus Foundation, of which I am a trustee, honored the film and the people whose story it tells so eloquently with a table at the James Beard Foundation awards dinner. |

With the film backed by Participant Media, and in tandem with many others working to end hunger in America, the Marcus Foundation hopes to use the movie as a platform to jump-start a renewed discussion of hunger in America that will lead to policy change to once again eliminate hunger in a nation abundant with food. (For more information, including a trailer of the film, see my dispatch: A Place at The Table.)

With authenticity in mind, it was not lost on any of us that honoring hungry people while dining on a gourmet meal is at best ironic and at worst obscene. Tables at awards dinners in New York City are not free; money spent on a table could feed many people. Was it right, just, appropriate? Are we walking the walk or just talking the talk? Time will tell whether our efforts to address hunger indirectly though story-telling, advocacy, and communications bear fruit and reduce hunger, or on reflection our funds would have been better spent feeding hungry people directly.

Another irony of the conference, this one sweet and poignant for me, was Wendell Berry reading out a web site address so that everyone could have access to his proposed 50-year Farm Bill: www.landinstitute.org. The bill is important reading, contains much wisdom, and is much shorter than the current draft farm bill still sitting in Congress. The irony is, as Wendell Berry acknowledged, that he has no computer. (Full disclosure: I was once a happy member myself of the now defunct Lead Pencil Society – with the motto, ‘not so fast’.)

If it is possible to have numerous first principles, then Wendell Berry has penned more than might reasonably be expected of any one man. He spoke eloquently at the conference and emphasized one of nature’s first principles that our species violates repeatedly in its rush to produce more, now, faster. “Keep the ground covered” is his admonition to all of us who want to continue eating not just today but also tomorrow. And for those who from ignorance or arrogance think of themselves as disconnected to the world of soil and sun and erosion and agriculture, he reminds us “eating is an agricultural act.”

If “food is our common ground” and “eating is an agricultural act,” then we are both literally and figuratively bound together by the soil that nourishes us, our food and our spirit. “Food deserts” are thus aptly named for the multi-level deprivation they occasion. And they are now well mapped online (see the USDA's Economic Research Service 'Food Desert Locator').

How can one have faith and trust in a nation so riddled with systemic and enduring injustice; so racked by inequality across so many levels? Simran Sethi, an award-winning journalist delivered a beautiful presentation in which she identified four building blocks of trust: predictability, reciprocity, vulnerability, and value exchange. Mapping these values across the stakeholders that struggle still with the deepest wounds that still exist in America would be an honorable undertaking. How can we develop these values such that people of means feel for and act such that they are trusted by people struggling in food deserts?

Applying these to the issue of GMO’s, discussed during Day I, it is no wonder that Monsanto remains an easy target – and that the target is easy does not mean it is any less deserving. If the figure cited by Daniel Ravicher from the Public Patent Foundation is correct, Monsanto spends $3,000,000 per day on legal fees. And one can reasonably surmise that much of this is related to their efforts around GMO crops to deny responsibility, display invulnerability; control value exchange, and hide beyond a mountain of secrecy.

Malik Yakini, Executive Director of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network and a 2012 James Beard award winner, was thus a breath of fresh air in speaking the truth about the enduring and debilitating presence of racism in America. He was right to observe that the conference room was almost all white. Yet, as a white, privileged, man I wonder if the room should be a demographic reflection of the country as Malik Yakini implied. Or, should it be an accurate reflection of the intended audience of thought leaders in the food sector? It is another, and very important question, whether the organizers (and I am on the James Beard Foundation conference steering committee) did a good enough job finding people of color who are thought leaders in this space.

Struck by his comment that no major grocery chains have stores in Detroit, something so gripping that I repeated it to a few people within hours, I decided I better research this a bit. While he is technically correct, the core of his solid position that we all need to hear and respect and act on seems to be undercut by this assertion. It seems Detroit is not in its entirety a food desert and has sizeable grocery stores – even if not owned by the national chains. While I am sure the situation is evolving, see James Griffioen's 2011 article "Yes, There are Grocery Stores in Detroit" in Urbanophile. Around a set of issues where great weight is given to the value of everything local, it is ironic that in depicting the great work that has been done in Detroit, locally owned supermarkets are not also considered part of the solution.

Another presenter, and one of the few celebrity chefs of color, Marcus Samuelsson spoke intensely about the work he is doing in Harlem that is an effort to “honor the past, be in the present and hint at the future.” James Beard and Wendell Berry, alongside the work of many others, can help us bridge the gap between farm and table. But looking into the future, who is going to help us answer the powerful question Marcus posed: “How do you train a server who has never dined?”

Far beyond the confines of a fine-dining restaurant, this question resonates from the devastated communities of Detroit to the glimmering office towers around Columbus Circle in New York City. How can we understand an experience we have never had? How can we cultivate empathy?

- jonathan.halperin's blog

- Log in or register to post comments