You are here

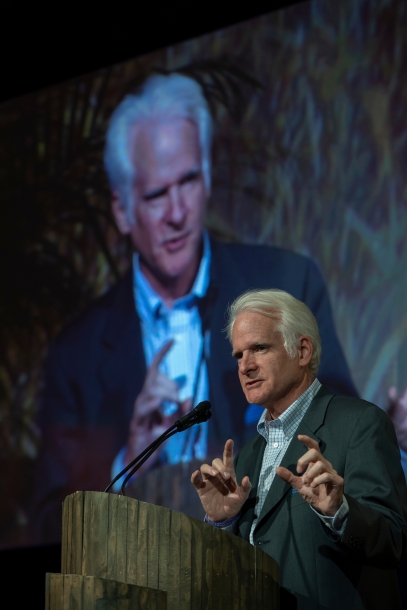

Trust and Risk: A Key Challenge for Today’s Leaders

Five years ago today, as the consequences of the Fukushima nuclear meltdown were still emerging, The New York Times published my letter observing that “trust comes not from repeated and paternalistic proclamations of success, but rather from the humble admission of mistakes followed by demonstrable changes in behavior and attitude.”

Trust remains at the core of business success. For leaders it is essential - but elusive. Frustratingly, it is often easier to see trust as it slips out under the closed doors of of the executive suite amidst a swirl of headlines about food safety, burst pipelines, boycotts, shareholder resolutions, or the defensive cover-up of what might have been a manageable error.

Trust is hard to measure; it doesn’t sit on anyone’s dashboard next to sales and safety data. Yet it is interwoven with brand value, organizational culture, recruitment and retention, license to operate, regulatory challenges, risk management, public affairs and so forth. Needed throughout an organization and across key relationships, it is rarely owned by a singular leader or department.

Part of the challenge of trust is that it cannot just be created and distributed at will. A “trust initiative” is a bit like the suggestion box that appears in the midst of controversy; too little, too late. I cannot create trust by myself. It is bestowed on me and my organization by others. Trust rests in the attitudes and actions of other people. I can build muscle mass by working out alone; to garner trust, on the other hand, I need other people working with me. The trust a business enjoys is essentially on-loan from vendors, colleagues, customers, investors and other stakeholders.

- Greyston Bakery, for example, has a huge cache of trust among critical stakeholders who believe in the mission of this pioneering benefit corporation that is the sole supplier of brownies to Ben & Jerry’s – and is widely recognized for its open-hiring program. Monetizing that trust is a welcome but tricky challenge for its top leaders.

- ExxonMobil, on the other hand, suffers from a huge deficit of trust and hauls that liability around as burden in every aspect of its business despite engineering prowess and cash-on-hand beyond compare. Long a target for members of its founder’s heirs, for its unwillingness to disclose information related to climate, the company now faces not only the Rockefellers as disgruntled investors but also a suit filed by Attorneys General from sixteen states.

How leaders and organizations behave clearly influences trust. Take food, beyond brownies, for example. No one would willingly eat food from a person or organization they did not trust. Chefs, thus, enjoy tremendous trust. Many have thus emerged as not just magnificently trained cooks, but as leaders in the efforts to improve the quality, access, and nutritional value of the food we eat – whether in restaurants, schools, corporate cafeterias, or airports. But as Chipotle has had to learn repeatedly, once trust is breached repair can be very costly.

When we trust fully, we put risk aside. But when we trust less than fully, risk re-enters our thinking and takes center-stage. Even if we don’t fully realize it, the questions we pose to ourselves in an instant are a form of risk assessment:

- Does that vendor seem reliable?

- How long has that food been sitting in the display?

- I am buying that line of argument; do I know enough?

In the developed world, we don’t want to think about eating as a risky activity – which it has been for most of the course of human civilization and still is for many with limited financial resources. When consumers call for “local” food, when shoppers search for food labelled “organic”, when survey respondents state a preference for “natural” products, and when millennials read labels to see if a product contains ingredients they cannot even pronounce; all of this is, at root, a search for trust.

If risk is the intersection of probability and consequence, then trust is a traffic circle that needs to be navigated with a clear realization that the views and actions of other players may be more important to our success than how we alone steer. To navigate this space, a few guidelines:

- Find the people who trust you least. Don’t try to change their views. Let them be scouts to help you identify vulnerabilities. Listen actively.

- Transparency is only half the story. Before looking for kudos, take responsibility and fix problems – and make sure the fixes are full rather than partial patches.

- If a problem is hard to fix or will take a long-time, be forthright and explain the situation.

- Be authentic when a partial fix is just that; don’t position a bandage as if its brain surgery.

- Manage trust like any other asset, but remember you don’t own it outright; it is a joint venture with stakeholders.

- jonathan.halperin's blog

- Log in or register to post comments