You are here

Cultivating Democracy Ecologically

September 24, 1989

Op-Ed

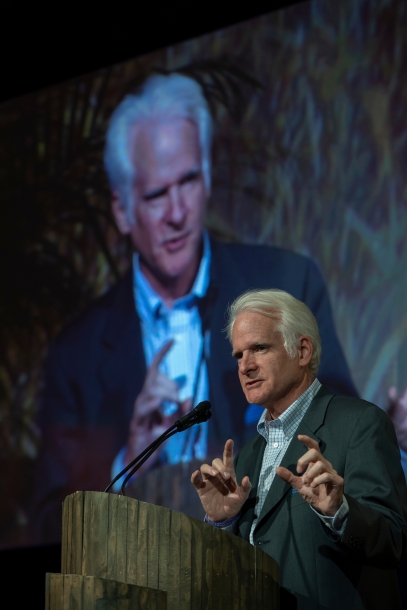

Jonathan J. Halperin

Permalink: http://articles.latimes.com/1989-09-24/opinion/op-179_1_soviet-union

Soviet People Can See, Taste and Smell Failures of Centralized Power

If Josef Stalin had cared for ladybugs, things might be different today in the Soviet Union. Mutations of these bugs are occurring 70 times more frequently around Lake Baikal, near the Mongolian border, than elsewhere in the Soviet Union. This obscure fact is symbolic both of how important ecology is to perestroika and of the historical and deeply rooted obstacles that stand in the path of the "revolution from above."![]()

One of the initiators of the infamous Baikal paper and pulp mill (identified as a cause of the mutations) was a close friend of Lavrenti Beria, Stalin's confidant and head of his internal security forces. As with much of what Mikhail S. Gorbachev and his supporters are revealing, and attempting, within the Soviet Union, Stalin's dirty fingerprints are evident in the battle over pollution control.

The issue of contemporary Soviet environmental degradation, while still rather obscure to most Western observers, is a dangerous social, economic and political irritant. It is exacerbating the severe and worsening shortage of consumer goods, the seeming intractability of Soviet agriculture and the appalling state of the Soviet health-care industry. Every wound and scab on the Soviet body politic is infected by toxic wastes, choking fumes and polluted waters across the country.

Food shortages, for example, are a direct result of past Soviet agricultural policy--years of monoculture planting, overuse of pesticides, Stalin's massacre of the successful peasant class and the brutal collectivization of agriculture.

More recently, immense damage has been done by monstrously ill-conceived "projects of the century," designed to reverse the flow of Siberian rivers and to connect rivers by enormous canals. One cynical Soviet story quips that the goal of the next (and the next and the next) five-year plan is to turn all swamps into deserts and all deserts into swamps.

The idiocy and catastrophic effect of such plans is perhaps most plain in Central Asia, where the Aral Sea once supported an active fishing industry. Now the sea's overall area has shrunk by about 40% because of the siphoning of irrigation water from its two key feeder rivers.

Ports and docks sit surreally amid sand dunes and desert landscapes. And the dry seabed, caked with salt and pesticides, disperses more than 65 million tons of its poisonous dust over thousands of miles every year. This has resulted in the poisoning of croplands and (by increasing the salt content of rain) hastened the melting of glaciers in the Pamir and Alta mountains.

Although Soviet economic and political leaders have gone to great pains to encourage Western assistance and business participation in rebuilding Soviet industry, opposition to joint ventures on environmental grounds is growing rapidly.

Major oil, gas and petrochemical projects are at risk because of fears over their ecological effects. Impact statements are being demanded, and officials have been berated publicly for overlooking the environmental records of Western partners. One article lashed out at the Western partners of a petrochemical development project in Tyumen, in Soviet Asia, stating that firms in the West will "gladly cut back on their energy-intensive and ecologically dangerous production, turning . . . Tyumen oblast (region) into a world latrine."

The disappearance of the Aral Sea and the disfiguring of Tyumen are at the top of a long list of environmental crises facing Soviet leaders. The issue also presents them with an attractive opportunity: Success can be tangible. People can see, taste and smell the difference between polluted and clean water; crops either grow or shrivel. Measurable achievements, urgently needed to ensure the success of perestroika, can be had in this arena.

The United States and American businesses thus have an important stake in the success or failure of environmental protection in the Soviet Union. Forces resisting such reforms represent the same interests threatened by the overall restructuring program: conservative Communist Party leaders and local party chieftains, bureaucrats and enterprises that seek to preserve their highly centralized power.

While the outcome is by no means certain--for perestroika or environmental protection--the battle has been joined by ministries, institutes and publications and by the hundreds of informal groups emerging from the long-unwatered and pillaged soil of Soviet political life.

If the Soviet power structure is to be successfully, albeit partially, dismantled and some form of enduring democratic activity is to arise "from the bottom up," then this impetus may well come from the environmental movement.

It is the people in these new groups who have been among the quickest to take advantage of what must already be counted as one of Gorbachev's most significant achievements: the creation of precious political space within which people, by their actions, transform themselves into citizens. Carved out of the poisoned soil of Soviet history, this space is being enlarged from above by Gorbachev and his supporters and strengthened from below by fragile but tenacious local environmental groups.

Jonathan J. Halperin is president of FYI Information Resources for a Changing World, a research-firm specializing in US-Soviet issues