You are here

Magic Realism in The Gulf of Mexico

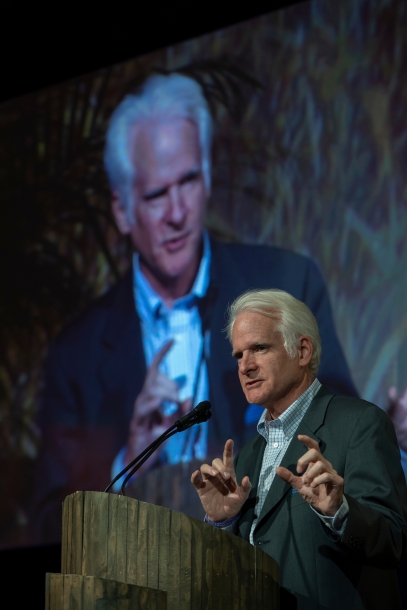

As part of the global marketing of Hope in a Changing Climate, the award-winning film Halperin executive produced with a team from the Environmental Education Media Project, Halperin authored a series of blog posts from December 2009 to June 2010. The following dispatch is part of this series.

To learn more about the film and ecosystem restoration, see the Hope in a Changing Climate project.

We are in an historical moment. So much needs to be said. Yet words seem so inadequate, so futile -- so much talk as oil explodes from the sea floor.

The pattern is all too familiar.

Lax government oversight of profit maximizing firms; technical, health, and environmental safety still treated as irritants in the way of the core business; minimizing the scale of destruction; independent science and government regulators slow to challenge corporate pronouncements; the collection and display of dead animals; intensifying recrimination, hearings, suits; battles raging on the airwaves, in the halls of Congress; people’s job threatened or lost; mounting frustration.

There are a few systemic absurdities worth noting in this disaster. Someone needs to perform an economic analysis of how much the offshore oil industry has invested, comparatively, in new drilling technology and in new safety technology. That we can now drill into reservoirs of oil that sit not only a mile under the sea, but also another 3 miles underneath the sea floor is mind-boggling. That our approach to planning for loosing control of such drilling continues to revolve around surface containment booms, burns, and skims is absolutely pathetic. With all due respect, but how hard is it to figure out that the environmental risk from such deep drilling efforts is fundamentally different from that of a surface spill from, just for example, a tanker off the coast of Alaska?

Related, booms make sense if one expects the oil to come to the surface in large quantities. Dispersants make sense, perhaps, as a technique for ensuring that large quantities of oil never make it to the surface – and onto beaches as well as televisions. But massive quantities of toxic dispersants flushed into the ocean a mile down and booms placed along the surface?

As a means of keeping the oil off the evening news by keeping the worst images of damage well below the surface, dispersants may be doing a very effective job. But as a path to mitigating long-term environmental devastation, this is nothing more than a cynical return to the most ignorant sophisms of the 1950s. We were told over and over and over that the lake, the river, the forest, the atmosphere [fill in the blank as you like] was big enough to absorb the pollution without significant damage. Then as now, far from resolving the problem, we are – language matters – dispersing it.

And what better name could possibly have been given to the oil field resting calmly miles below the oceans surface, ensconced in its geologic tomb only to be punctured by BP’s drill? Macondo; the fictional name used by the master of magic realism, Gabrielle Garcia Marquez, to describe his birthplace.

Nalco seems to have wholly embraced this literary genre when searching for product names. The two chemical agents (9500A and 9527A) that disperse the oil bear the fantastical name of – Corexit. Of course, it does nothing of the sort, but no matter, it surely cannot do any harm itself. As stated on Nalco’s website that characterizes but does not name the seven ingredients in Corexit, a third ingredient is found in a popular brand of baby bath liquid,” and “put another way, COREXIT 9527 is more than 7 times safer than dish soap.” And if that is not reassurance enough, Dr. Manian Ramesh, Chief Technology Officer for Nalco, provides the details we really need to feel good. He explains that “dispersants work on an oil spill as dishwashing detergent works on a greasy skillet: they break up oil into tiny droplets that sink below the water's surface where naturally occurring bacteria consume them. Without dispersants, oil stays on the water's surface, where bacteria can't get at them.”

The pattern is all too familiar.

-- Jonathan J. Halperin