You are here

Bad Deal, Good Deal, No Deal

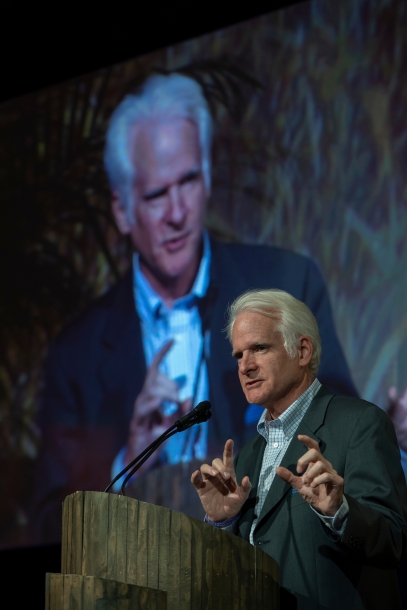

As part of the global marketing of Hope in a Changing Climate, the award-winning film Halperin executive produced with a team from the Environmental Education Media Project, Halperin authored a series of blog posts from December 2009 to June 2010. The following dispatch is part of this series.

To learn more about the film and ecosystem restoration, see the Hope in a Changing Climate project.

After listening to the head of the United Nations Environment Program, Achim Steiner, say, in regard to the negotiations here in Copenhagen, that “we are losing faith, we are losing trust, we are losing confidence, we are getting angrier with each other, and we are beginning to lose the sense that we can do it,” I pondered possible outcomes. The lack of an agreement would represent a profound failure for all involved, and there are thus tremendous incentives to avoid this — especially with the signals sent in the ramp-up to the process: American, Chinese, Indian, and Brazilian announcements.

But the incentives can also have a perverse effect if they drive the world into a bad agreement, committing parties either to unachievable commitments, deeply inequitable ones, or merely face-saving statements of intention. While The Kyoto Protocol has usefully driven us as a people to belatedly address the risk of an increasingly unstable climate, so too are its failures useful cautions for what we attempt now.

Again, Steiner, speaking as part of Yann Arthus-Bertrand’s GoodPlanet Film Festival at the Danish Film Institute:

“In the sense that the Kyoto Protocol and Cap and Trade have created an imperative to begin to price carbon, it has been a success story … The difficulty [now] is that as of tomorrow, with heads of State arriving, you suddenly find yourself in this very dangerous zone, that politicians hate to leave without a result. But the groundwork hasn’t been completed. The building blocks are not ready. So you get into very volatile political territory, where people may suddenly either do a deal because they want to have something to take home, and it’s a very bad deal for the climate change agenda — or things get so frustrated that the meeting basically says ‘there is no deal.’ And this is perhaps where it’s up to you to decide if a good deal, a bad deal, or no deal is the preferred option.”

But one positive outcome seems all but certain, unless it unravels in the next 48 hours. And that is the further inclusion of natural ecosystems into the framework for addressing climate change. Until now, the vast bulk of attention and procedure has been dedicated to addressing human activities. But there is clearly increased recognition that REDD (or REDD + or REDD ++, in the arcane of COP15) is going to be central to effectively stabilizing atmospheric greenhouse gases. The mechanisms for monitoring, verification and financing, as well as the vast organizational challenges of effective governance and accountability still require intense effort. But it is now clear that protecting existing forests (avoiding deforestation, as it is known) and planting new forests (developing new reservoir from aforestation and reforestation for natural sequestration of carbon) are going to be more fully recognized and financially valued in the aftermath of COP15.

Despite the overall outcome of this climate conference, beyond the positioning of failure or success, aside from the deep and real questions of whether we are doing too little too late, it seems likely that we are at a turning point. As a species, we are today articulating in the clearest of terms a coming of age in our relationship to ecosystems. Perhaps, we are the end of the beginning of an age were Pogo can be turned on his head. Perhaps tomorrow we will be able to say that while “we have met the enemy,” he is not so much us — today – as our past behavior.

As with the snow that swirled into Copenhagen this morning, so too has the natural role of ecosystems come center stage here in the Bella Center.

-- Jonathan J. Halperin